The Schenectady police union has gone to court in an attempt to conceal the disciplinary record of an officer caught on camera driving his knee into the neck of a local Guyanese man suspected of misdemeanor criminal mischief in July.

State Supreme Court Justice Mark Powers issued a temporary restraining order stopping the release of Officer Brian Pommer’s disciplinary file sought by Albany Proper.

The order was spurred by a lawsuit filed Sept. 3 by the Schenectady Police Benevolent Association on Pommer’s behalf, which seeks to block the release of a notice and any unsubstantiated or non-final complaints or charges in his file.

A hearing has been scheduled for later this month.

A certain “counseling notice” and a draft “notice of potential charges” appear to be a matter of importance for the PBA and Pommer. Power’s order, which applies at least until the Sept. 23 hearing, specifically prohibits the city of Schenectady from releasing the documents until he hears arguments in court and makes a determination.

Schenectady Corporation Counsel Andrew Koldin cited the restraining order in a Sept. 11 letter denying Albany Proper’s Freedom of Information request for Pommer’s disciplinary records. The initial lawsuit filing is also sealed from the public as a result of this order.

According to Schenectady Police Department’s Guidelines for Investigating Officer Misconduct, counseling notices “may be used by the supervisor to determine if the member is familiar with a particular issue or aware of the Department’s written directives, policies or procedures, that govern members behavior and to determine further training needs.” With records sealed, it’s not clear if this notice was the result of misconduct.

A ‘SECRET SOCIETY’

For years, Section 50-A of the New York State Civil Rights Law made it possible for disciplinary actions to remain sealed.

Joel Berger, a lawyer with the New York City firm of Sonnenfeld & Richman, has spent decades fighting the hypocrisy he has seen as a result of 50-A. First as a staff attorney with the New York City Law Department before entering private practice representing civil rights clients with New York City Legal Aid Society Prisoners’ Rights Project and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

“When cops are investigating a potential criminal they don’t just look at convictions, they look at charges,” he said. “And that’s understandable given the infirmities of the criminal justice system. They want to see if some guy has been accused of something. They want to see what he’s all about.”

“But when it cops, god forbid unless it’s been convicted in a disciplinary proceeding and punished, and even then, they oppose the release.”

“It makes no sense at all.”

Berger describes police officers as a “secret society.”

“In terms of secrecy and circling the wagon, taking care of everything in-house and never going to outside agencies to investigate — that hasn’t changed,” he said. “It really hasn’t changed in 50 years.”

Berger recalls a case early in his career when he handled lawsuits in the New York City prison system. An opposing lawyer for the city told him, “you think representing corrections is hard? You should see what happens when I try to represent the cops. They won’t tell me a goddamn thing.”

In June, the New York State Legislature repealed 50-A, which police departments had used for years to shield officers’ misconduct and disciplinary records from public scrutiny. It was a part of a push for criminal justice reform by the newly elected Democratic majority in the state legislature and nationwide calls for action.

The “blue wall of silence” was finally coming down.

However, despite the change in law, police unions across the state have gone to court in an attempt to keep the wall up.

Schenectady joins the likes of New York City, Buffalo, and Tonawanda, where police unions have also sued the municipalities they serve in an attempt to block the release of unsubstantiated or non-final complaints.

Berger doesn’t see the lawsuits standing on solid ground for much longer.

“The unions are down to the last gas,” he said. “It’s a last ditch effort to prevent the inevitable.”

INCIDENT PUT SPOTLIGHT ON POMMER

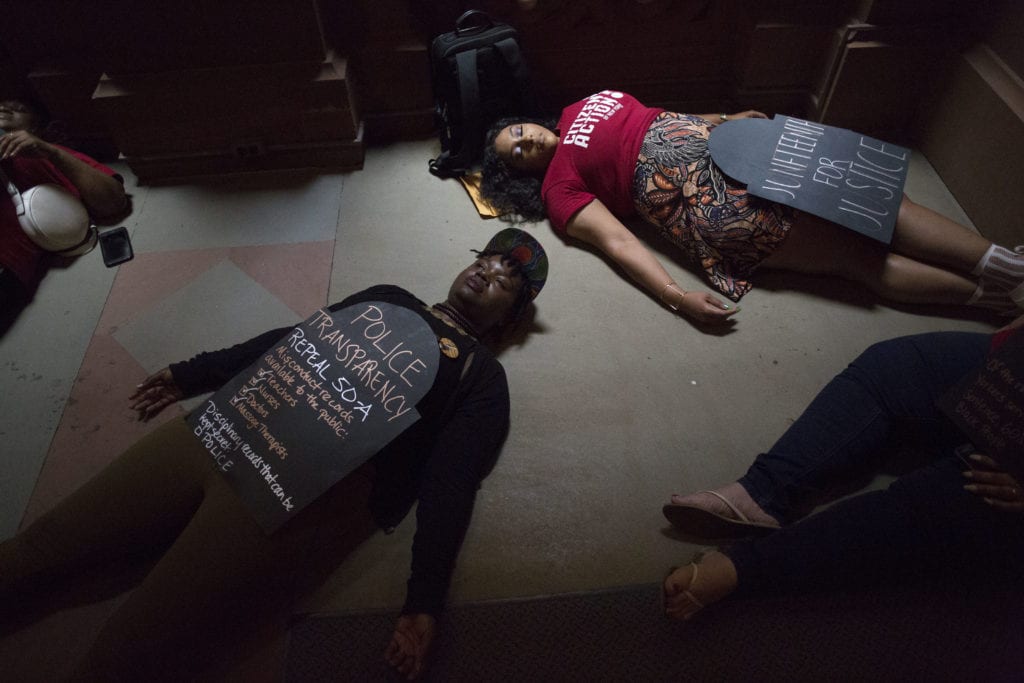

Back in July, Yugeshwar Gaindarpersaud arrived at Schenectady Police Headquarters in rough shape — a hospital bracelet still on his wrist, a bandage from an IV across his arm, and a bright red bruise on his forehead. He lifted up his shirt and shorts to show more bruises.

Gaindarpersaud told the dozens of local activists who gathered in his support that the injuries were the result of an arrest by Officer Pommer in his own backyard earlier that same day.

Video eventually released by the city shows Officer Pommer questioning Gaindarpersaud for only 14 seconds about a claim made by his neighbor that he slashed her tires. Tensions rise as Gaindarpersaud asks to see surveillance footage allegedly showing the crime. Pommer then demands that he place his hands behind his back, never telling him what he is being charged with and making little attempt to de-escalate the situation.

After a brief chase down the driveway, you then see Officer Pommer tackle Gaindarpersaud and force his knee on his neck in an attempt to restrain him. Pommer also repeatedly yells “put your hands behind your fucking back” while punching six times at the rib cage. Gaindarpersaud cries out in pain under the officer’s weight throughout the encounter.

“If he had me for five more minutes on the ground,” Gaindarpersaud said, “I’d be gone.”

The incident that played out in Schenectady was just 42 days after a similar knee-to-neck restraint killed George Floyd in Minneapolis and set off months of Black Lives Matter protests across the country. Since then, Governor Cuomo has mandated that towns and cities across the state ‘reimagine’ policing, threatening to withhold funding unless local authorities approve police-reform plans by April.

Before the Schenectady department released body-camera and dashboard video, the city was already in damage control. Chief Clifford urged patience as his department investigated the incident, saying in a statement that “at no time did the officer try to impair Mr. Gaindarpersaud’s breathing or blood circulation.” Mayor McCarthy told the press that he would be waiting for more video to be made available, despite widely circulated cellphone video recorded by Gaindarpersaud’s father at the scene.

Chief Clifford further defended his officer’s actions by claiming that the officer’s knee was actually on Gaindarpersaud’s head and not on his neck. He later berated local activists, led by community group All of Us, in a tweet while they staged a protest in front of city hall:

I have shown this community my willingness to discuss reforms @schdypolice , have made efforts to engage conversations, and remained patient during a month of peaceful protests. That all ends tonight. No more disorder in the city. https://t.co/3PEYzTMMGG

— Chief Eric S. Clifford (@CliffordChief) July 14, 2020

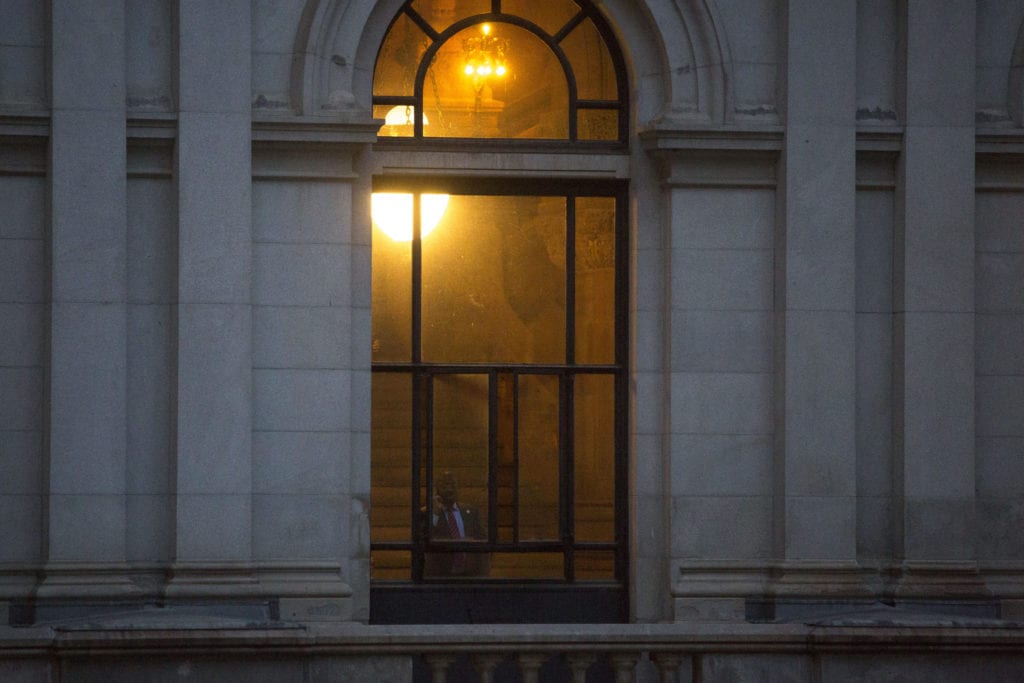

The night that Chief Clifford declared disorder in the city, protesters had surrounded the exterior of an empty City Hall with calls for police accountability. Groups sat in front of the entrances and exits, speaking into megaphones while more marched around the building.

As the hours went on, dozens of pizzas were ordered from nearby Pizza King. Dance circles formed.

Protesters were settling in for a long night.

At around 8:30 P.M. a caravan of police vehicles sped to a halt outside the rear exit of City Hall. The door of a white van flew open to reveal officers dressed in riot gear.

They were there to extract three officers that had been stationed inside the building. The crowd of protesters, many of whom had been sitting on the grass eating pizza prior to this, confronted them and mobilized into the street as the officers made their getaway.

It was the first they had seen of the police, or any city official, that evening.

Fearing that police were mobilizing to disperse them, protesters locked arm and arm. Instructions were given to put on masks and goggles if they had them.

There they stayed link arm and arm late into the night, but police were not seen again.

Following public demonstrations by All of Us, the mayor and chief announced new changes to an executive order, including banning knee to neck and head restraints and further protocols for warrant-less arrests and de-escalation training.

Officer Pommer was placed on desk duty. A request made to the police department to see if Pommer still remains on desk duty went unanswered.

A SEAT AT THE TABLE

Despite active litigation, the PBA was also given a seat at the table for a city task force on ongoing police ‘reimagining’ discussions. Other members of the task force include Mayor Gary McCarthy, Police Chief Eric Clifford and representatives from the Schenectady Civilian Police Review Board, the Schenectady NAACP, the Schenectady Hindu Temple & Guyanese Community Center, and All of Us.

Jamaica Miles, co-founder of All of Us, said she was not surprised after learning about the lawsuit.

“The conflict of interest alone boggles my mind,” she said. “Not only is the PBA interfering in an investigation, which our city has a right to do, but they’ve also now inserted themselves into the process of our task force.”

Shawn Young, also a co-founder of All of Us, sees this as an attempt by the union to subvert the repeal of 50-A.

“If there is something on his record that is harmful or that points to a pattern of behavior, then the people should have access to that,” he said.

“Any attempt to block that speaks to the culture of the police department and its union in wanting to protect itself.”

- Stream the Patrick Porter tribute show – January 21, 2026

- Patrick Porter remembered as a creative force – June 30, 2025

- Protomartyr and Fashion Club at No Fun – June 13, 2024