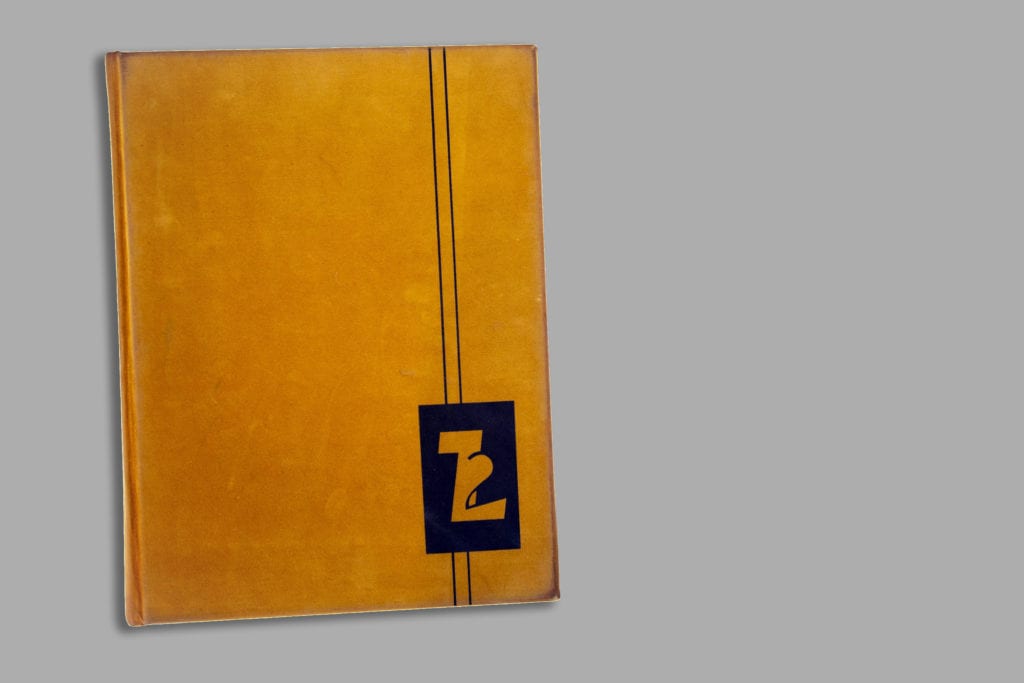

When Shane Aslan Selzer was a teenager she stumbled upon her parent’s college yearbook tucked away on a shelf. What she found was more than just funny haircuts and vintage shirts — she found a time capsule from one of the most radical and progressive times in United States history.

It was a time that she discovered looked eerily similar the present.

“I had never seen anything like it, I looked at it late at night, for years and showed it to any friends who would show interest,” Selzer said. “It was a radical document I had stumbled upon that felt like a guide to living.”

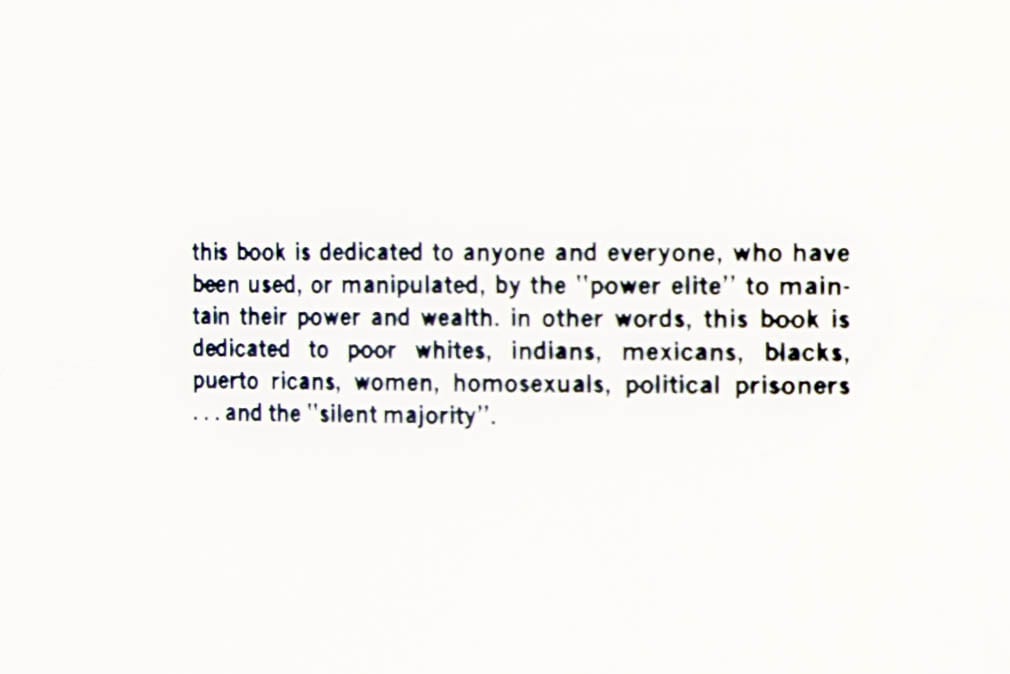

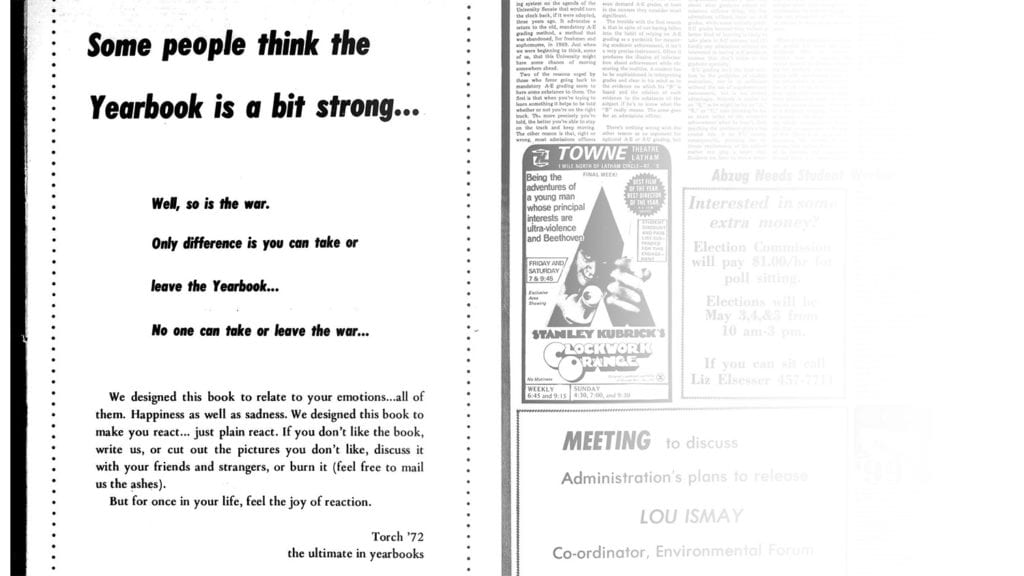

A new exhibit at UAlbany’s University Art Museum, curated by Selzer, takes a look at this controversial yearbook. The exhibit “explores the trajectory and lineage of intersectional justice efforts on the UAlbany campus, and reactivates UAlbany’s 1972 Torch yearbook, edited by then student and renowned AIDS activist, Ron Simmons.”

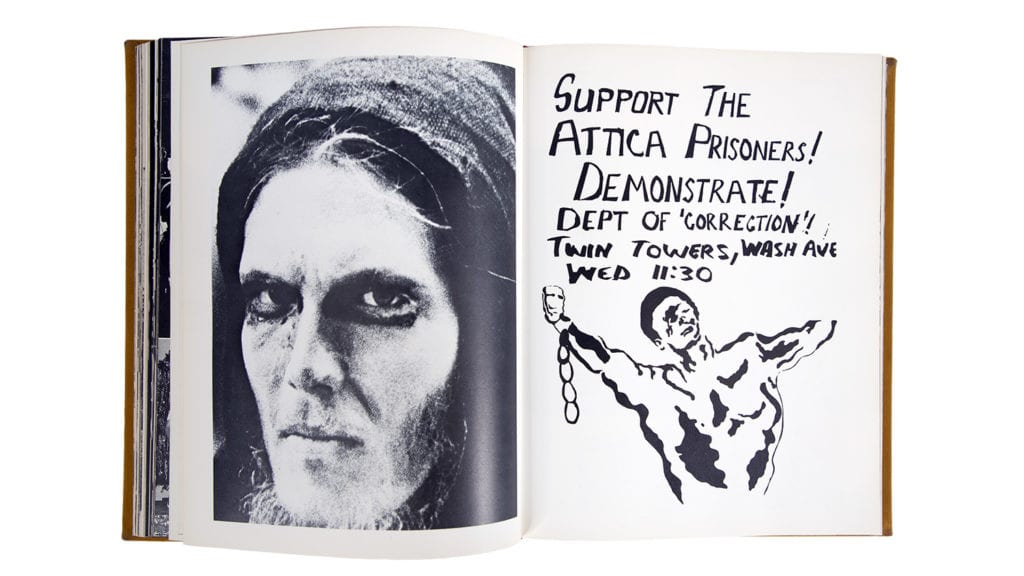

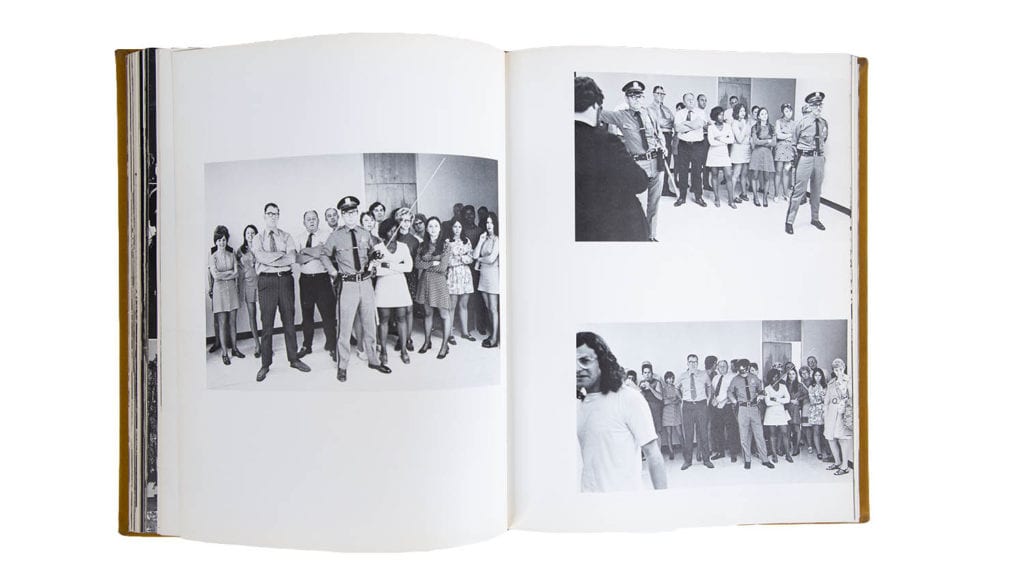

One of the most shocking elements of the 1972 Torch Yearbook is the senior portrait section, which inter-disperses images of an unidentified North Vietnamese soldier’s decapitated head among the senior portraits. Simmons kept the plan a secret until it was published, and backlash is said to have extended as far as a member of the New York State Assembly protesting to the book during a legislative session.

Inside the book, Simmons challenges the viewer to “…look at these pictures, and ask yourself; why? Look within yourself, and see if you feel any emotion, any ‘discomfort’…and if you do, try to imagine how they must feel.”

The final pages of the yearbook offer tear-out pages to send reactions to the book, and ads placed in the Albany Student Press following its publications explained the meaning behind the shocking images. In addition to his work with Torch, Simmons also wrote a column called “Faggotales”, arguably the first column written specifically from a Black gay male perspective, for the school newspaper. Those writings are now archived by the New York Public Library.

Since the 70’s, public opinion of the book (and the war in Vietnam) has shifted. World-renowned photographer Martin Parr told Time Magazine that it was the best photobook about America, saying “one of the unsung achievements of American publishing are the college annuals.”

Melissa ‘Bunni’ Elian, a former Chief Photographer for Torch Yearbook, is interviewed as part of the exhibit, telling Selzer, “if we didn’t see those things, Americans wouldn’t have been horrified. The difference with today, particularly with Black pain, is that we’re too used to it. It’s kind of like, oh this is the way it is, and it has less of an effect. I think it’s still jarring, but it just keeps happening.”

In addition to images from the book itself, the exhibit features video and audio interviews from current student leaders on campus, “using the 1972 yearbook as a visual prompt to speak about the trajectory and lineage of intersectional justice efforts on the UAlbany campus.”

Albany-based videographer Adam Muro filmed current Torch Yearbook students flipping through the pages of the book for their first time. Selzer combines this footage with a poem by UAlbany student Fanta Ballo, who was awarded the first Shawn Mendes Foundation and Google ‘Wonder Grant’ last year.

Torch’72/2020 *feat. Pain by Fanta Ballo (excerpt from two channel video projection. TRT 13:25) from Shane Aslan Selzer on Vimeo.

This evening the University Art Museum and current students are hosting a conversation via Zoom, “Students Speak: A Dialogue about Art, Activism, and Museums as Social Spaces.” Registration to join the discussion is online here.

Torch ’72/2020 is on display through April 3, 2021 and COVID-precaution reservations are open to the campus community online at www.albany.edu/museum, or by calling (518) 442-4035..

Prior to his death last year, Simmons exchanged emails with Albany Proper to discuss his path following the yearbook.

“I had a jazz column in a local paper in Harlem and was running with the music critic crowd, going to concerts, receptions and press parties. At one of the parties, I realized that I was carrying heavy equipment, and worrying about f-stops and light levels, etc. while the journalists were enjoying their drinks and conversation. There was something wrong with the scene, namely me working hard while the writers were enjoying themselves. I stopped taking pictures, just wrote the music column, and started enjoying the press parties.”

Simmons did continue to photograph black activists involved with the gay liberation movement from the 1970’s through the 1990’s. He donated 600 of those slides to the Smithsonian National Museum for African-American Culture.

His work only expanded after he put the camera down. Simmons would eventually go on to build Us Helping Us, People into Living, Inc., an HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care services organization that specializes in services for Black gay and bisexual men. He was awarded the University’s Harvey Milk Award in 2010.

“The struggle continues,” he said.

Note: the author of this article is an employee of UAlbany, a former editor of Torch Yearbook, and a contributing artist to the exhibit.

- Patrick Porter remembered as a creative force – June 30, 2025

- Protomartyr and Fashion Club at No Fun – June 13, 2024

- Sheer Mag at No Fun – May 5, 2024