This article originally appeared on Them+Us Media

An outspoken Albany restaurant owner wants to help at least 10 West Hill and Arbor Hill neighborhood residents purchase property by the end of this year.

Kizzy Williams expects to reach that goal by providing homeownership, lending, credit, and savings education outside a modest Amish-made wooden shed at 64 Quail Street. Opening Tuesday, the 41-year-old entrepreneur believes that the Cultural Center could help bolster a community ravaged by decades of discriminatory divestment.

“You’re going to have more strength to get up in the morning and do something for yourself,” Williams said. “This is what owning a property does. It makes you feel important.”

The shed’s small scale and clean design stands out like a waffle in a stack of pancakes in the downtrodden West Hill scene. Williams has a different take on the 28 by 64-foot lot: it adds love to the long-vacant street corner.

By the age of 45, she hopes to acquire and revitalize at least 30 lots across the city.

“Not only am I willing to pay for these empty lots,” Williams said. “I’m willing to put the resources there to keep it clean.”

Grassy empty lots and abandoned buildings are scattered across the predominantly Black West Hill and Arbor Hill neighborhoods. There are more than a quarter of derelict properties within blocks of Williams’ Clinton Avenue business, Allie B’s Cozy Kitchen.

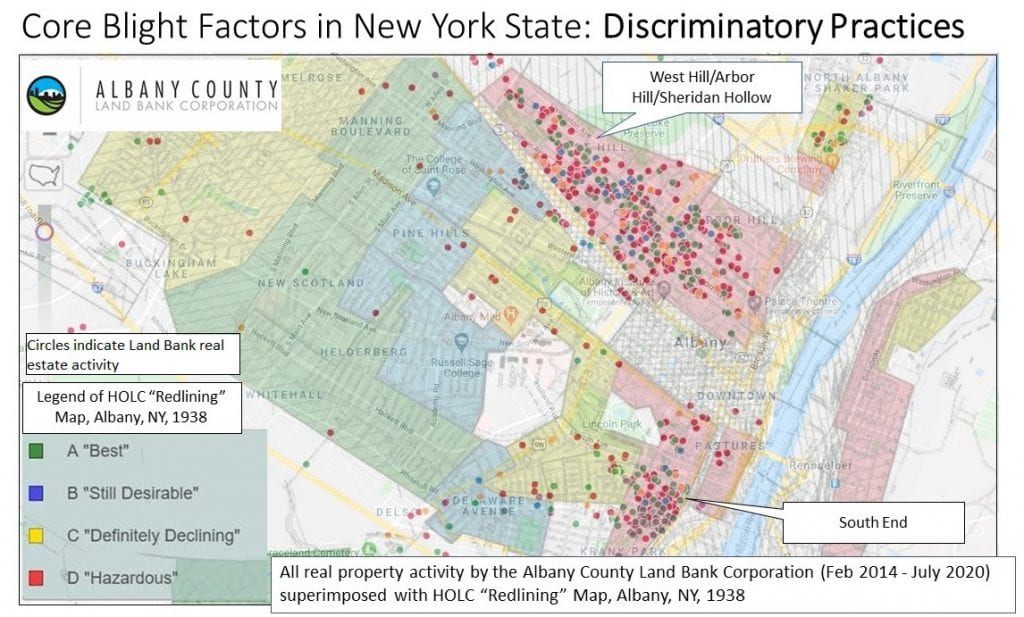

The roots of urban decay stretch back to the 1930s when neighborhoods of color were redlined — deemed to be a risk to mortgage lenders and home insurance providers. Even after the practice was prohibited in the 1970s, the initial divestment caused subsequent generations to struggle in poverty, many unable to afford or maintain housing.

According to U.S. Census Bureau data from 2010, more than 30% of the Arbor Hill area population lives below the federal poverty line. Only 25% of in-use properties are owner-occupied. Outside, residents frequently witness boarded-up abandoned buildings labeled with a Red X, a hazard warning for first responders.

“Let me tell you, when I see the Red X, I see pain,” Williams said. “I see a community that’s been taken advantage of.”

Launching Allie B’s Cozy Kitchen in 2014, Williams lived on food stamps in a government-subsidized apartment on Clinton Avenue with two sons. She was previously a housekeeper living on an $8.75 hourly wage.

Since growing up in a Harlem public housing complex during the 1980s and 1990s, Williams dreamed of buying her own property. Buoyed by the success of her restaurant, she finally bought a house in Cohoes with her wife three years ago.

It’s not a common story for residents. The Albany metro area has the second-highest racial homeownership gap in the nation behind Minneapolis. An American Community Survey report conducted between 2012 and 2016 found that nearly 70% of whites in Albany County owned their home, while only a fifth of their Black counterparts did.

A proud homeowner, Williams was convinced that a positive example of land ownership in West Hill or Arbor Hill could inspire residents to revitalize properties of the like throughout the community.

She bought the Cultural Center property for $5,000 in June. The corner lot has long been surrounded by poverty and crime, including a recent drive-by shooting that injured two people. Williams wants to change the negative narrative.

“When someone thinks wrongly of Quail Street, First Street, Livingston Avenue, they think wrongly of me,” Williams said.

The building’s name, she explained, represents the area’s cultural influences. Williams originally wanted to have a pagoda to display solidarity with Albany’s emerging Southeast Asian population, but couldn’t afford it. She eventually wants to deck the shed with Asian decor.

Community groups, including West Hill’s Refugee Welcome Corporation, are pushing to resettle refugees in the neighborhood’s vacant and abandoned buildings. The RWC currently houses more than 100 people in the area.

“We cannot make change without them — these young and intelligent refugees,” Williams said.

An ambitious social justice activist and personality in the community, her initiative has the support of groups including Albany County Land Bank, Building Blocks Together, and the National Congress of Black Women.

Local housing consultant Virginia Rawlins believes Williams’ effort can help undo the devastating effects of redlining. Rawlins founded One Block At Time, an Albany-based advocacy organization aimed at uplifting impoverished communities through homeownership.

“I think it’s important that [Williams] didn’t keep it as greenspace because now she’s changing the market so nothing in that area looks like the Cultural Center,” Rawlins said. “She’s planting the seeds that you can buy a lot from the land bank or private owner and give that land more value than what you initially imagined.”

The Albany County Land Bank was formed in 2014 following a flurry of foreclosures that happened in the aftermath of the Great Recession. The organization manages the transition of tax-foreclosed, vacant, and abandoned properties to bar predatory speculators and absentee landlords from acquisition.

From 2014 to 2019, the land bank seized 228 lots and sold 99 lots in Arbor Hill and West Hill. In the same period, the group seized 105 buildings and sold 66 buildings in the abutting neighborhoods.

Many residents often have enough money to buy properties from the land bank, according to the public authority’s executive director Adam Zaranko, but legal and state-mandated closing costs can make a sale pricey.

The group’s screening process can be a double-edged sword. It prevents predatory buyers from outside the area, Zaranko said. “But at the same time, it’s not unreasonable to say that our screening process also can create barriers for residents that have less resources to acquire the lot.”

Looking for a lower cost, Williams originally tried to purchase a property through the Albany County Land Bank. She ultimately chose to buy a lot from a private owner after facing back-to-back barriers in the screening process.

Zaranko hailed the restaurant owner’s input as a critical part of working to ease the acquisition process for neighborhood denizens.

Despite her disappointment, Williams isn’t finished pursuing vacant lots in the city’s northern quarter through the Albany County Land Bank. Looking at Orange Street and Henry Johnson Boulevard, she’s reached out to the public authority about buying land for an outdoor library as well as a safe space for residents to play board games.

She isn’t the only interested buyer nearby. According to Williams, other residents have shared lot revitalization ideas since she bought the Quail Street property.

“You want [properties] to go back responsively so there’s a lot of ways to do that,” Zarenko said about Williams’ influence. “And I think that we don’t know most of them, so we need those ideas.”

About the grand opening:

The grand opening is on Tuesday, Aug. 11 from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Visitors are required to stay socially distant out of COVID-19 fears. The grand opening is designed to direct guests from the front yard to the back exit in an effort to avoid crowding.

The grand opening and early workshops will be free. Williams expects to eventually cement a “nominal” fee to pay for property costs and upkeep.

- Rt. 7 corridor gathering a blissful moment for seasoned organizer – April 19, 2021

- Emotions soar amid sudden, unfenced tree clearance in Lincoln Park – April 12, 2021

- Here’s how a superhighway changed one road in Rotterdam – August 11, 2020