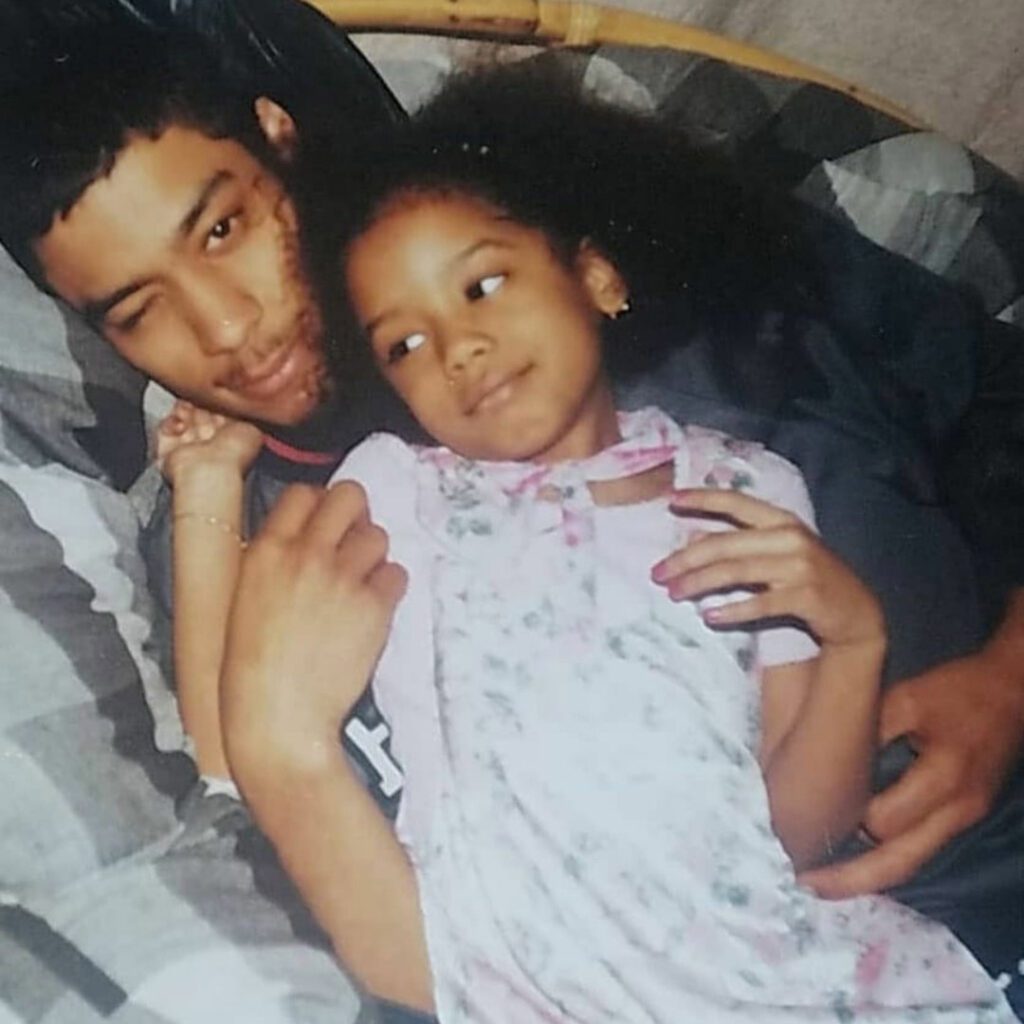

TeAna Taylor was just a child when her father went to prison.

Now 27, she has seen him transform, undergoing drug treatment, therapy and counseling, taking parenting classes, mentoring younger, incarcerated men, facilitating a restorative justice program and attending college through the Cornell Prison Education Program and the Bard Prison Initiative.

“He harmed countless people, he harmed countless families,” said Taylor, a lifelong Schenectady resident. “But he has since done all he can to rehabilitate himself, to become the best person he can, the best father he can be.”

Convicted of second-degree murder in 2005 and sentenced to 22 years to life, Leroy Taylor, 47, will be eligible for parole in four years.

His efforts at rehabilitation might make him seem like a strong candidate for parole, but there’s no guarantee he’ll get it.

“My dad is not just his crime,” said Taylor, who serves as co-director of communications and policy for the Release Aging People from Prison Campaign. “But it’s likely the only thing the parole board will look at is the nature of his crime.”

The RAPP Campaign is part of a broader coalition, the People’s Campaign for Parole Justice, that is pushing the state Legislature to reform New York’s parole system, with the goal of seeing more people return to their communities to rebuild their lives outside prison walls.

This is a worthy objective.

It should be easier for people who have used their time in prison to change for the better to get a second chance. And while some might blanch at the idea of granting parole to people convicted of violent crimes, there are plenty of compelling reasons to do so.

Redemption is possible, as Albany Proper’s recent article on Albany resident Mfame Sikivu makes clear.

Granted clemency by former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Sikivu founded a self-improvement organization aimed at keeping youth out of trouble while still incarcerated, and now runs it out of a shop on Quail Street.

There’s also research to suggest that almost all criminals, even violent ones, age out of lawbreaking before middle age.

According to an op-ed by the non-profit news site The Marshall Project, which focuses on criminal justice issues, “criminal careers do not last very long. Research by the criminologist Alfred Blumstein of Carnegie Mellon and colleagues has found that for the eight serious crimes closely tracked by the F.B.I. – murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny-theft, arson and car theft – five to 10 years is the typical duration that adults commit these crimes, as measured by arrests.”

The piece adds, “In short, a sentence that outlasts an offender’s desire or ability to break the law is a drain on taxpayers, with little upside in protecting public safety or improving an inmate’s chances for success after release.”

The New York State Legislature ought to make reforming the state’s parole system a priority by passing two bills, Fair and Timely Parole and Elder Parole.

Fair and Timely Parole would require the state parole board to grant parole to any incarcerated person who is eligible, unless the person presents an unreasonable risk that cannot be mitigated with supervision.

The Elder Parole bill would require that a person who is 55 years or older be considered for release by the parole board if they’ve served at least 15 years of their sentence.

According to a report released last year by the Center for Justice at Columbia University, titled “Unlocking Billions,” Fair and Timely Parole and Elder Parole would save a significant amount of money – $522 million annually – by reducing the state’s prison population.

Another goal shared by parole reform supporters such as the RAPP Campaign is overhauling the state’s clemency process. Gov. Kathy Hochul granted clemency to just 10 people at the end of 2021 – a disappointment to criminal justice advocates.

Only one of the individuals pardoned by Hochul was in prison – a man named Roger Cole, who returned to his home country of Jamaica upon his release. The other pardons were issued to immigrants who were already out of jail but might have faced deportation as a result of their convictions.

Hochul did call for reform of the clemency process, and announced plans to set up an advisory panel to assist the governor in reviewing clemency applications.

Taylor said she’s hoping the governor will take the issue seriously.

“We’ve been pushing for clemency to be more frequent, inclusive and transparent,” she said. “We’re looking to Gov. Hochul to do what Cuomo failed to do – to use clemency as a tool to address the crisis of aging and death behind bars.”

Clemency and parole are tools that can work in tandem to ensure that people don’t languish behind bars any longer than necessary.

Before the pandemic, New York’s parole release numbers were trending upward, from 10-15% of applicants to 35-40%, according to the People’s Campaign for Parole Justice.

“Unfortunately, this upward trend reversed during the peak of the pandemic, and the Parole Board is now reviewing fewer cases and releasing fewer people when they should be accelerating decarceration in the interest of health and safety,” the PCPJ observed.

In mid-January, state Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli weighed in on the topic, calling on policy makers to look for opportunities to reduce the population of incarcerated individuals age 50 and above.

A report released by the Comptroller’s Office noted that “older incarcerated individuals are generally more costly to accommodate and care for, primarily due to their greater medical needs.”

Though health care costs for all incarcerated individuals in New York prisons are trending downward along with the State prison population itself, they remain a significant burden to the State at about $350 million per year, the report states.

The money saved by releasing prisoners who pose little risk to the public is a persuasive reason to support Elder Parole and Fair and Timely Parole.

Even more persuasive is the benefit to society from allowing people who have found redemption to return home, reconnect with their families and share what they’ve learned.

Staying close to an incarcerated parent isn’t easy.

“We weren’t always able to see my father,” Taylor recalled. “When he was in Auburn, he was three-and-a-half hours away. It was difficult to get there.”

In Taylor’s mind, reformed prison inmates such as her father are some of the best people to teach youth about the potential consequences of a life of crime, and should be given the opportunity to return to their communities and put their knowledge and talents to use.

“My father has helped people in prison who are now out, and they’ve told me how much he helped them,” Taylor said. “And the reason he was able to do that is because other elders did the same for him.”

- Coalition addresses ‘period poverty’ in Schenectady – December 8, 2022

- West Hill is a food desert. This market works to change that. – October 21, 2022

- DakhaBrakha concert in Schenectady a must-see event – July 31, 2022